By Beverly James, Alec Richman, Brad Buck, Samantha Grenrock and Tom Nordlie

The year was 1917. In April, the United States entered World War I. Florida’s population was fast approaching 1 million, and agriculture was the state’s most important economic driver.

Citrus cultivation, introduced to Florida 400 years earlier by Spanish explorers, had spawned an industry following the Civil War. By 1917, oranges were the state’s most valuable food crop, followed by field corn with grapefruit a close third.

Florida growers produced 8.2 million boxes of citrus during the 1916–17 season, most of it sold fresh, with small amounts devoted to canning. Production had been shifting away from North Florida for 20 years, and Central Florida was now dotted with groves. Most oranges came from the “citrus belt” that ran from Ocala southwest to Bradenton and southeast to Fort Pierce. Grapefruit was most common along the southeast coast. Cold-tolerant satsumas were the only citrus widely grown in the Panhandle.

Despite steadily increasing yields, Florida’s citrus industry had not yet achieved its economic potential. Growers tended to work independently and often addressed production problems with trial-and-error methods. In Gainesville, University of Florida (UF) researchers were already investigating citrus issues but faced logistical obstacles in contacting growers. A citrus canker outbreak that began in 1912 showed no signs of abating, a hard freeze in February 1917 had damaged the year’s crop and, conversely, oversupply was an ongoing issue that held down farm-gate prices.

FOUNDING THROUGH 1920s

In June 1917, state leaders recognized the value in providing citrus growers with modern, scientific methods. On June 4, the Florida Legislature authorized creation of an off-campus UF research facility, soon dubbed the Citrus Experiment Station (CES). The authorization required that the facility be located in Polk County and be supported by $10,000 in private funding. By summer 1919, growers had raised more than the required amount. UF secured an 84-acre tract of land just north of Lake Alfred, which included 14.5 acres of established groves.

On Oct. 1, 1920, CES gained its first employee, John H. Jefferies, who supervised the groves and lived in a cottage on-site. One of Jefferies’ immediate concerns was establishing a budwood supply grove where growers could obtain top-quality scions from the CES collection. He also assisted UF researchers in setting up field experiments, which were previously conducted in Gainesville or in commercial groves in Tavares. A $10,000 appropriation from the legislature in 1923 helped cover construction, equipment and supplies.

In 1926, the first UF faculty member — plant pathologist W.A. Kuntz — was stationed at CES full-time. He initially focused on the fungal disease citrus melanose. That same year saw construction of a greenhouse, a permanent laboratory and an insectary for rearing the ladybeetle Harmonia axyridis, which was selected for an aphid biocontrol study. Early CES personnel developed a seasonal calendar of citrus pests and appropriate management tactics. They also helped resolve two crises: a 1929 outbreak of the highly destructive Mediterranean fruit fly near Orlando and a 1934 outbreak of citrus blackfly in the Keys.

1930s

By 1935, CES had five full-time staff members. Three events took place that year to ensure the station’s long-term survival. First, UF leaders decreed that all of the university’s future citrus research would take place at CES. Next, the Florida Legislature approved an annual appropriation of almost $47,000, ensuring adequate funding for expansion. Third, grove superintendent Jefferies retired and horticulturalist Arthur F. Camp became the first CES director to work on-site.

Researchers were publishing nutrition recommendations by the early 1930s, including a 1930 assessment of soil acidity throughout Florida’s popular Central Ridge growing region and a 1931 bulletin assessing the usefulness of low-cost synthetic fertilizers, a new invention. But in 1937, CES released a milestone: a study on micronutrients demonstrating that applications of zinc, manganese and magnesium could improve yield. Growers confirmed the finding with increased yields, and micronutrients quickly became a permanent aspect of Florida citrus cultivation.

1940s

The 1940s were a pivotal decade for CES, marked by extensive growth brought about by World War II. When the U.S. Armed Forces needed a palatable vitamin C supplement for troops stationed overseas, they turned to Florida orange juice. For three growing seasons beginning with 1942–43, the federal government purchased about 20 percent of the entire U.S. citrus crop. Prices reached new heights, prompting growers to plant additional acreage.

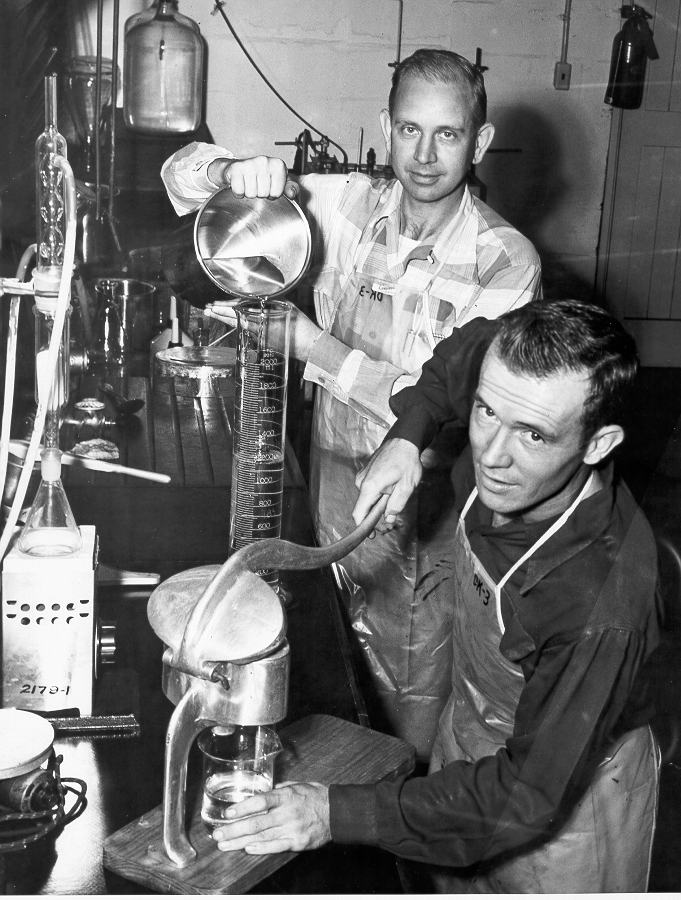

One of the developers of frozen orange juice concentrate was University of Florida alumnus C.D. Atkins, seen on the left.

At CES, growth this decade spanned infrastructure, land and personnel. A library was established, and new construction included a packinghouse research building and a processing building. Moreover, in 1949, CES established a field laboratory in Indian River (now Indian River Research and Education Center) on an 80-acre tract, giving greater attention to the area’s grapefruit operations. The CES staff numbered 10 in 1943, and that number tripled by the end of the decade.

During the war years, Florida-based scientists worked feverishly to develop methods of condensing and freezing orange juice so that it could be reconstituted later. Although the project was primarily carried out in Lakeland by employees of the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) and the Florida Citrus Commission, some work took place at CES and involved UF horticulturalist A.L. Stahl.

The effort was spurred by the realization that Florida’s citrus crop would flood the market when the war ended, and massive government orange purchases presumably would stop. The technology to make frozen concentrate was patented in November 1948 and provided free of charge to producers. The product itself was an immediate hit with consumers. By the 1949–50 season, Florida produced 20 million gallons of concentrate. The resulting demand for juicing oranges not only ended oversupply concerns, but drove up farm-gate prices and spurred further planting. In the 1950–51 season, Florida harvested 100 million boxes of citrus for the first time.

Scientific progress was made on numerous fronts. Research on frozen concentrated orange juice continued at the station, to improve the product and adapt to changes in varieties and consumer preferences. In 1940, the station initiated post-harvest research, which led to new degreening processes that were less costly and more environmentally friendly.

Plant pathologist E.P. DuCharme spent several years studying citrus tristeza virus in Argentina in anticipation of its possible arrival in Florida, an early example of pre-emptive international research. In 1945, a CES team began investigating spreading decline, a mysterious and often fatal citrus malady. The scientists concluded that the causal agent affected the root system, but they could not isolate or identify it. Fortunately, the team would make great strides toward ending the threat of spreading decline in the 1950s and 1960s.

1950s

As with the previous decade, the 1950s were characterized by expansion of the Citrus Experiment Station in an effort to keep pace with industry growth.

In retrospect, perhaps the decade’s most surprising innovation was a 1951 project exploring supplemental irrigation for citrus, which had been considered largely unnecessary. It would soon prove to be a vital factor in maximizing yields. Also in 1951, pruning studies gave rise to development of experimental hedging machines at CES.

But the most remarkable advances of this period concerned plant pathology. Researcher Ivan Stewart conclusively demonstrated in 1952 that the condition known as yellow spot resulted from molybdenum deficiency. After he sprayed affected trees with sodium molybdate, their symptoms disappeared within weeks. In 1953, researchers determined that spreading decline was caused by the burrowing nematode, which created lesions in the deep feeder roots of infested trees. This discovery laid the groundwork for effective control in the 1960s.

Citrus yields climbed ever higher — the 1954–55 harvest was 136.9 million boxes — and expansion continued at CES. In 1953, the station boasted a staff of 50. In 1955, CES acquired an additional 255 acres, including 40 acres of groves in nearby Davenport. The CES entomology building was completed and occupied in 1958. There was also a change in leadership – Arthur F. Camp retired as director on Dec. 31, 1956, succeeded by Herman J. Reitz on Jan. 1, 1957.

In the latter half of the 1950s, two more innovations took hold. One was a research program examining the feasibility of mechanical citrus harvesting as a cost-cutting measure. The other innovation was a renewed interest in citrus breeding, motivated by the need for new rootstocks that were less vulnerable to the burrowing nematode. In time, the station would become the source for a number of rootstock varieties, many of them tolerant of or resistant to industry-crippling diseases.

1960s

As Florida’s citrus industry grew, so did the significance of the challenges that growers faced from nature. This principle was made abundantly clear in the early 1960s.

In September 1960, Hurricane Donna destroyed half of the state’s grapefruit crop. June 1962 saw a Mediterranean fruit fly outbreak, and then a severe freeze occurred Dec. 12–13, 1962. The year 1964 brought with it the first Florida reports of Diaprepes citrus root weevil in September. Two months later, a false alarm concerning Oriental fruit fly prompted extensive, unnecessary surveys in Hillsborough and Manatee counties.

But throughout the 1960s, CES researchers dug deeper to develop scientific innovations and help resolve more of the industry’s lingering production issues. For example, horticulturalist A.P. Pieringer and his team scored a decisive victory in the battle against spreading decline — the most serious citrus disease Florida faced in the 1950s and early 1960s — when they released two rootstocks that were resistant to the burrowing nematode. These new rootstock options, combined with cultural practices and nematicides, effectively suppressed spreading decline by the decade’s end.

Following the 1962 freeze, growers continued to relocate further south, and many of them established operations in southeast flatwoods areas with poorly drained soils. To protect the groves from flooding and moisture-loving fungal diseases, CES researchers worked with contractors to optimize grove drainage systems, reduce clogging within pipes and ensure acceptable flow rates.

In another move toward greater efficiency, CES researchers conducted extensive field trials on fertilizer and recommended that growers stop using so-called “low-analysis” fertilizer, which sometimes contained 50 percent sand by weight. New “high-analysis” fertilizers contained less filler. Growers who switched typically saved 50 to 75 percent on fertilizer costs.

In the early 1960s, the station also evaluated herbicides and made recommendations, laying a foundation for the industry’s current weed-control practices.

The use of oils for pest control became a research concern and led to effective treatment against the malady known as greasy spot, which had hindered production since the 1940s. A research program undertaken at the station in the late 1960s soon revealed that greasy spot was caused by the fungus Mycosphaerella citri and could be controlled by spraying trees with a petroleum-based oil, or oil plus copper, during summer months.

1970s

Many observers consider the 1970s the heyday of Florida citrus. In 1970, the state’s citrus production reached an all-time high of 941,000 acres. The 1971–72 season saw the harvest surpass 200 million boxes for the first time. Decades of hard work by CES researchers were paying off.

In 1971, the station was renamed the Agricultural Research and Education Center to comply with a university-wide policy change.

Scientists gained a better understanding of the citrus rust mite, which had periodically impacted Florida citrus since the 1870s. By the late 1960s, researchers had determined that they could use the fungus Hirsutella thompsonii to control the mite. This was one of many natural enemies that were being studied by Martin Muma, who conducted innovative biocontrol research at the station in the 1960s and 1970s.

Another disease familiar to Florida growers, Alternaria brown spot, was caused by a fungus. A Florida outbreak in 1973 led to development of management recommendations released by center plant pathologists in 1976. Incidence of the disease rapidly subsided afterward.

Florida growers had been relatively unimpeded by cold weather since 1962, but then a hard freeze occurred Jan. 18–20, 1977. The 1976–77 harvest topped 250 million boxes nonetheless, but the event served as a preview of weather woes the growers would face in the upcoming decade.

1980s

The 1980s saw six severe freezes devastate Florida’s citrus industry, one each in 1981, 1982, 1983, 1985 and two in 1989. For years, growers had used multiple methods to protect trees and crops, such as oil-fired heaters, wind machines and even blankets. But in the 1980s, the center began testing a less expensive and more effective approach: microirrigation.

In the 1980s, Citrus Research and Education Center personnel developed techniques for using microirrigation in freeze protection.

Unlike the overhead irrigation systems growers used to water trees during droughts, microsprinklers are placed at the base of each tree. In freeze protection, microsprinklers are used to generate a thin coating of ice on the tree’s trunk and lower limbs. Due to a physics phenomenon called latent heat of fusion, the ice can maintain coated tree tissue at approximately 32° F and protect it from lower temperatures.

Researchers at the center began investigating microirrigation in 1981 and found that it was more efficient than other freeze-protection technologies because it used less water and could be used to deliver fertilizers. Within a decade, microirrigation had become the most common cold-protection tool among Florida citrus growers. This technique has been a major factor in minimizing tree mortality.

Also during the 1980s, UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS) citrus researchers began devoting greater attention to sustainability issues. They studied the use of reclaimed, treated municipal wastewater for irrigation, demonstrating that it was safe and effective for irrigating citrus groves and even provided beneficial micronutrients. Center personnel helped plan the Water Conserv II project, the world’s largest program using reclaimed water for citrus irrigation, which became operational in December 1986.

The 1980s marked several milestones for the facility, as well. In March 1982, Herman Reitz retired. In August, Walter J. Kender was appointed director. That same year also saw the dedication of a multipurpose meeting and educational building, Ben Hill Griffin Jr. Citrus Hall.

In 1984, the Agricultural Research and Education Center became the Citrus Research and Education Center (CREC), a name that better reflected its mission to educate the next generation of citrus scientists. Previously, there were no classes offered at the center and no way for students to live and study in Lake Alfred. That changed with the construction of dormitories and establishment of six graduate-level courses on-site.

1990s

In the 1990s, growers found themselves battling an old foe that unexpectedly returned — the bacterial disease citrus canker.

Florida’s first recorded canker outbreak lasted from 1912 to 1933, and the disease was not reported again until 1986, when it was found infecting a dooryard citrus tree in the Tampa Bay area. This new outbreak spread to a commercial grove and was not eradicated until 1994. One year later, the disease was discovered in Miami-Dade County, and a new control effort began.

During these outbreaks, CREC researchers collaborated with USDA and the Florida Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services to improve control methods. They approached the problem from several angles. For example, researchers learned to distinguish between strains of canker and discovered how the bacterium infects trees, a process exacerbated by damage from the invasive citrus leafminer. Scientists also learned how the canker bacterium spreads over large geographic areas. This insight helped inform state and federal policies designed to curb canker transmission.

Like citrus canker, citrus blight is a disease with widespread economic impact. In 1991, CREC scientists developed a quick and reliable assay for citrus blight that involved sampling trees for proteins associated with the disease. In 1995, the threat of citrus tristeza virus escalated with the arrival of the brown citrus aphid in Florida. Consequently, growers began shifting from sour orange rootstock to varieties less vulnerable to the disease.

Best management practices helped reduce the citrus industry’s environmental footprint beginning in the 1990s.

Disease management was not the only aspect of citrus production that saw the introduction of new practices. In 1995, CREC faculty collaborated with USDA-Agricultural Research Service to publish the first edition of the handbook, Nutrition of Florida Citrus Trees. It advocated sustainable fertilization and gave growers the tools to increase production while protecting soil and water quality.

Financial support of CREC reached a milestone in 1990 with the establishment of the J.R. and Addie S. Graves Endowed Chair in Citrus Biotechnology by the Graves family of Wabasso, Florida. In 1992, citrus tristeza virus expert William O. Dawson was appointed as Graves Eminent Scholar. Toward the end of the decade, CREC had another change in leadership — entomologist Harold Browning was promoted to director in November 1996, following the retirement of Walt Kender.

2000s

As the 21st century began, citrus canker continued to hold its dubious distinction as the industry’s top disease concern. At CREC, researchers investigated the bacterium, and Extension personnel launched a statewide Citrus Canker Education Program to promote public awareness and good sanitation practices.

However, hurricanes in 2004 and 2005 spread the canker pathogen so extensively that in January 2006 USDA halted its eradication program. This move ended mandatory destruction of citrus trees located near infected specimens. However, growers had little reason to celebrate — in August 2005, Florida had its first reported cases of HLB-infected trees. As with citrus canker, HLB is a bacterial disease native to Southeast Asia that renders fruit unmarketable. Unlike canker, HLB eventually kills infected trees and is transmitted by an insect (the Asian citrus psyllid), which had been established in Florida since at least 1998.

As word of HLB spread, CREC faculty worked together with other statewide citrus specialists to gather information about HLB outbreaks abroad and to develop management recommendations specific to the Florida situation. These included reliable methods for producing disease-free citrus nursery stock, scouting methods for identifying infected trees in the early stages of infection, and spray programs for controlling the Asian citrus psyllid. CREC personnel also increased outreach efforts to educate growers, industry personnel, policy-makers and the public on these short-term approaches to managing HLB while research got under way to develop long-term solutions needed to win the battle with HLB.

2010 TO PRESENT

As 2010 dawned, HLB had already been the top concern at CREC for half a decade and would remain so to the present day.

The Asian citrus psyllid relentlessly spread HLB across the state’s citrus-producing regions. According to one CREC study, grower estimates collected in March 2015 indicated that 80 percent of commercial citrus trees statewide were infected.

Because HLB infections progress slowly, infected trees may continue to produce marketable fruit for years. Therefore, production was affected incrementally. Florida’s total citrus harvest for the 2011–2012 growing season was 170.9 million boxes; over the next five years, it declined to 156.2 million boxes, 124.0 million boxes, 112.7 million boxes, 94.2 million boxes and, finally, 78 million boxes in 2016–2017.

At CREC, many of the decade’s major HLB-related research and Extension efforts focused on methods for discouraging infections and minimizing damage by optimizing tree health with innovations such as pH-adjusted irrigation water and use of frequent low-dose applications of water and nutrients to the root system of HLB-infected trees. Other studies evaluated potential HLB treatments, such as injections and steam treatments intended to kill the pathogen within infected trees. The Citrus Health Management Areas (CHMA) program implemented by CREC helped growers reduce local psyllid populations by coordinating the timing of their insecticide applications.

Although many growers carried on, some chose to cease operations and sell their land. Ironically, land purchasers sometimes facilitated HLB’s spread by leaving groves untended and creating “safe harbors” for psyllid populations, as demonstrated by a CREC study published in December 2010. Other discoveries by CREC researchers this decade included the fact that the early stages of HLB infections cause the greatest damage in citrus roots, and the revelation that Asian citrus psyllid populations were developing resistance to commonly used insecticides.

Despite their constant focus on the HLB crisis, CREC faculty and staff members made progress in other areas this decade.

Breeding efforts reached a new high, following the 2010 release of the first CREC-bred scion cultivar, LB8-9, also known as Sugar Belle®. Thanks to one pioneering citrus grower, it was planted commercially and has since proven to be the most HLB-tolerant citrus variety grown in Florida; consequently, it is grown more widely today.

The first CREC-bred sweet orange release followed shortly thereafter with SF14W-62, also known as Valquarius®, a mid-season orange with Valencia juice quality that ripens at least six weeks earlier than Valencia. Since that time, the releases from the program have been accelerating, with a total of more than 30 scion and rootstock cultivars available to Florida growers. These releases include many seedless and easy-to-peel mandarins, a grapefruit hybrid that produces sweeter fruit and does not interact with medications, sweet oranges to extend the season with very high-quality juice, several rootstocks that impart greater tolerance of HLB to trees, and lemons with improved processing attributes.

Additionally, the program has led the way in developing applications of citrus biotechnology and has spearheaded global citrus genome sequencing projects, to support the development of disease-resistant, productive and high-quality new citrus varieties. Since 2010, more than 1 million new citrus trees utilizing these new rootstocks and scions have been planted in Florida, and that number continues to increase rapidly.

In 2009, Harold Browning stepped down as CREC director and longtime colleague Jackie Burns was named interim director. Two years later, Burns became permanent director. When she was promoted to UF/IFAS dean for research in November 2014, CREC entomologist Michael Rogers took over directorship duties, and holds the position today.

Uncertainty has been a hallmark of Florida’s citrus industry, and it’s too early to predict whether HLB will be defeated during the remaining years of this decade. Nonetheless, Rogers and his colleagues remain optimistic about the future of the Florida citrus industry. Not only will they find solutions to address today’s challenges, they are always poised to meet the challenges of tomorrow, just as the CREC faculty and staff have done for the past 100 years.

Beverly James is director of public relations; Alec Richman, Brad Buck, Samantha Grenrock and Tom Nordlie are public relations specialists — all with University of Florida Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences Communications in Gainesville.

Share this Post